Substance Use During Pregnancy and Family Care Plans

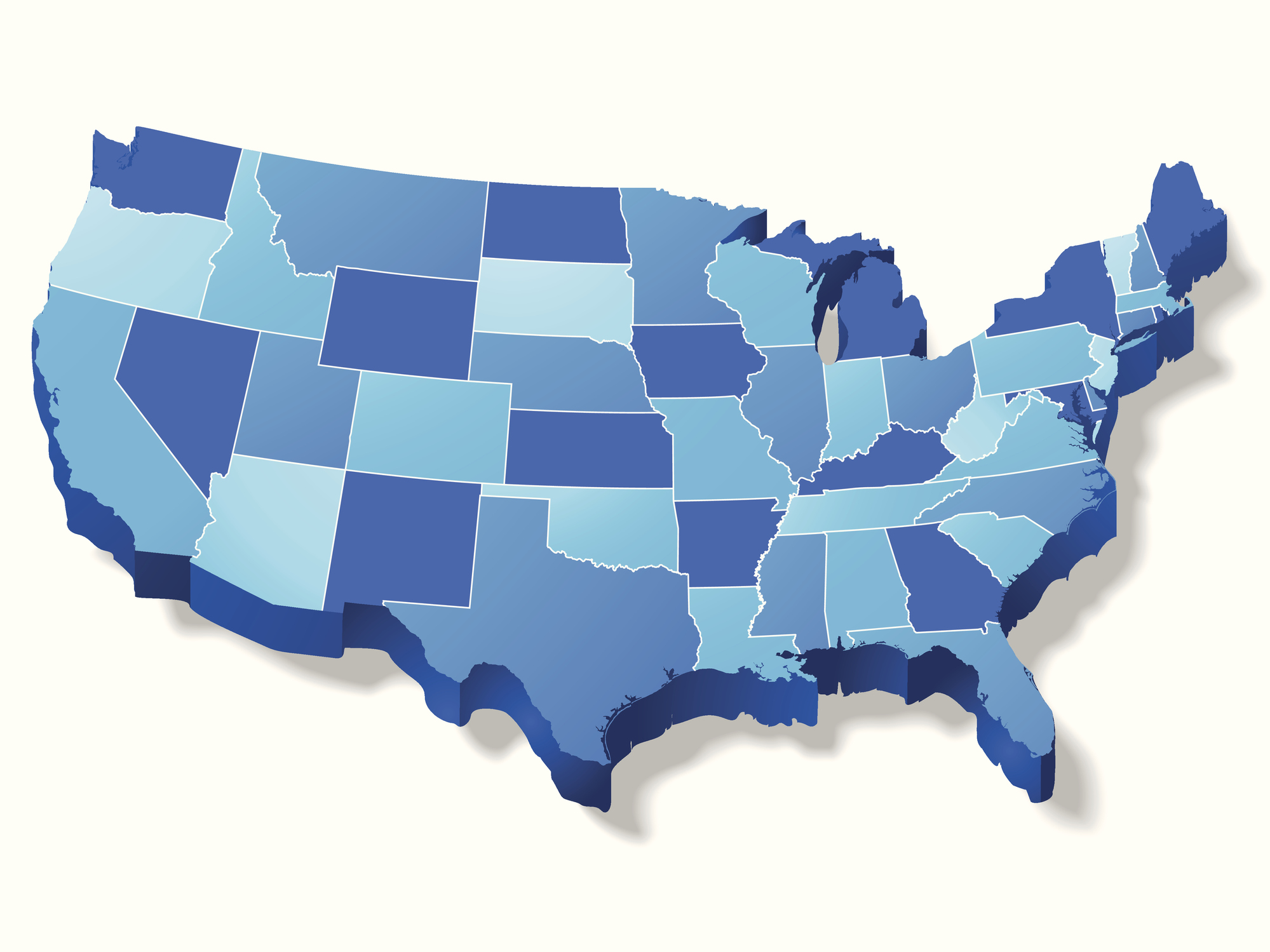

states assist pregnant or postpartum individuals with substance use disorder in seeking help by having specific laws/regulations designed to help families with substance-exposed infants and not automatically considering substance use during pregnancy or giving birth to a substance-exposed infant to be child abuse or neglect, as of September 2023.

What are supportive and non-punitive family care plans, and why are they important?

If a jurisdiction receives federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) funds, it must have procedures in place that mandate a healthcare professional involved in the care or delivery of an infant affected by substance abuse or withdrawal symptoms to notify the state or local child welfare agency of the birth of such infant.[1]42 U.S.C.A. § 5106a. CAPTA does not require the notification to contain any identifying information. CAPTA does, however, require that a family care plan be created for each infant for whom a notification is submitted.

Family care plans, also known as plans of safe care, are intended to be a non-punitive, collaborative, interdisciplinary, and responsive approach to ensuring the health and well-being of parents with substance use disorder (SUD) and infants born affected by parental SUD.[2],Johanna Catherine Maclean, et al., Prenatal Substance Use Policies and Infant Maltreatment Reports, 41 Health Affairs (Project Hope) 703–712 (May 2022), https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01755.[3]Model Substance Use During Pregnancy and Family Care Plans Act (Model Act), Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association (Nov. 2022), https://legislativeanalysis.org/substance-use-during-pregnancy-and-family-care-plans/. When child safety is not a concern, family care plans offer a pathway for families to receive services and provide population-level tracking to increase resources to higher-need communities.[4]Heather Briscoe, et al., Do No Harm: Rebuilding Trust & Keeping Families Together, Aces Aware (Oct. 2021), https://www.acesaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/DoNoHarmFinal.pdf. These plans link families to services such as substance use, mental health or other medical treatment, peer support services, and social services.[5]Model Act, supra note 3.

Punitive approaches to substance use during pregnancy are harmful and ineffective

Punitive responses to substance use during pregnancy increase stigma, reinforcing the belief that pre-natal substance use makes an individual unfit to be a parent.[6]Andrea Weber, et al., Substance Use in Pregnancy: Identifying Stigma and Improving Care, 12 Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation 105–121 (Nov. 2021), https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S319180. Medication for addiction treatment (MAT), such as buprenorphine or methadone, is highly effective in improving the health of the pregnant individual and the fetus.[7]Elizabeth E. Krans, et al., Outcomes associated with the use of medications for opioid use disorder during pregnancy, 116 Addiction 3504–3514 (May 25, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15582. However, only 19 states have created or funded drug treatment programs for pregnant people.[8]Substance use during pregnancy, Guttmacher Institute (July 1, 2023), https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/substance-use-during-pregnancy (as of August 31, 2023, the resource is offline “being updated and will be available again soon”).

In addition, in 25 states, substance use during in pregnancy is classified as child abuse[9]Id. and may result in the removal of the child from the home. Research shows, however, that children placed into foster care have significantly worse health and well-being outcomes than children in similar situations who are not removed from the home.[10]Trauma Caused by Separation of Children from Parents: A Tool to Help Lawyers, Children’s Rights Litigation Committee of the American Bar Association Section of Litigation (Jan. 2020), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/litigation_committees/childrights/child-separation-memo/parent-child-separation-trauma-memo.pdf.

Policies that criminalize, rather than treat, substance use during pregnancy also amplify other inequities. Black and Indigenous families are generally overrepresented in the child welfare system,[11]Disproportionality in Child Welfare: Fact Sheet, National Indian Child Welfare Association (Oct. 2021), https://www.nicwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/NICWA_11_2021-Disproportionality-Fact-Sheet.pdf. and Black parents are less likely to be reunified with their children once removed from the home.[12]Maria X. Sanmartin, et al., Association Between State-level Criminal Justice-focused Prenatal Substance Use Policies in the US and Substance Use-related Foster Care Admissions and Family Reunification, 174 JAMA Pediatrics 782–788 (May 18, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1027.

Supportive policies reduce family separation and encourage the use of more appropriate resources

Formal child protective services response pathways are often not tailored to the needs of substance-impacted families, and existing responses can often be ineffective. By creating separate pathways for families to access care through family care plans, states can reduce stigmatization and redirect individuals to more appropriate resources. Research also emphasizes the importance of keeping infants with the birthing parent immediately after birth and through infancy to improve short- and long-term outcomes.[13]Jeannette T. Crenshaw, Healthy Birth Practice #6: Keep Mother and Baby Together- It’s Best for Mother, Baby, and Breastfeeding, 23 The Journal of Perinatal Education 211–217 (Jan. 2014), https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.23.4.211.